This spring I made plans to meet friends from junior high school who I had not seen for years. I went through collections of old photographs to look for images of our youthful faces back in the seventies to help us reminisce. I found a number of poorly composed, out of focus, faded pictures that only the people featured in them could enjoy and appreciate. There was one that stood out from the rest, a sharp, clear, black and white photo snapped by my father, of me and our smooth haired fox terrier, Samantha.

This spring I made plans to meet friends from junior high school who I had not seen for years. I went through collections of old photographs to look for images of our youthful faces back in the seventies to help us reminisce. I found a number of poorly composed, out of focus, faded pictures that only the people featured in them could enjoy and appreciate. There was one that stood out from the rest, a sharp, clear, black and white photo snapped by my father, of me and our smooth haired fox terrier, Samantha.

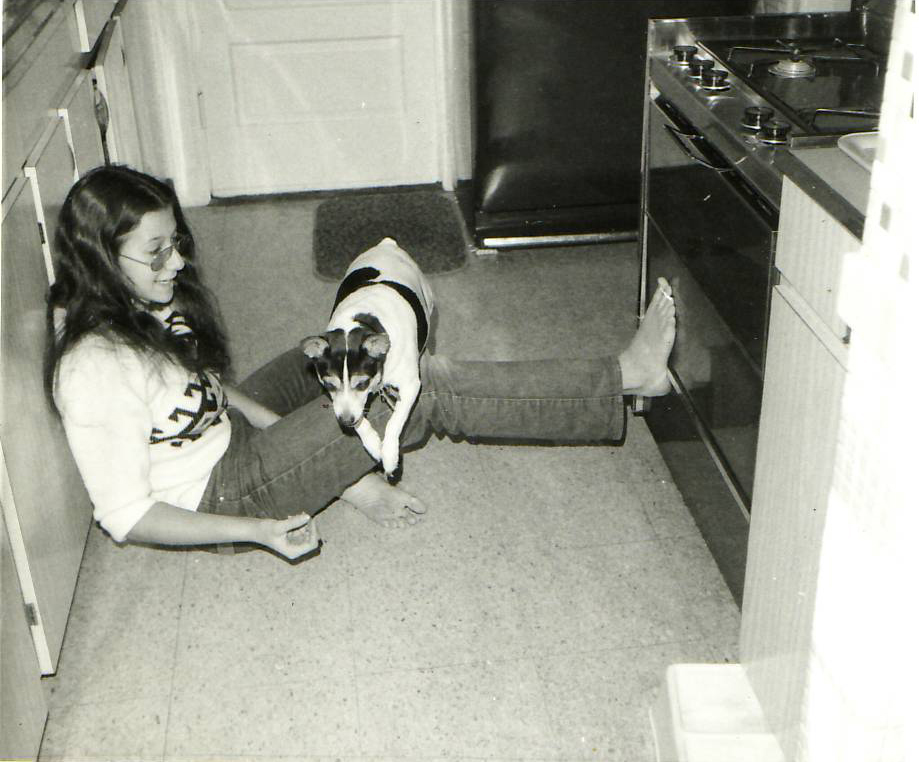

At age thirteen I am sitting on the floor in our kitchen, my back against the cupboards with one leg raised and slightly bent with my bare foot pressing against the stove door opposite me. My dark hair is long, and my bespectacled, smiling gaze is aimed downward at Sam as she sails over my raised leg. Sam had been captured in mid flight, heading toward the camera, her ears alert, her physique still relatively lean.

It is possible to see that I am holding my hand, with a treat, on the side of my leg I want Sam to leap toward. I had, without any instruction discovered lure training, having initially tossed treats over my leg to get her jump my personal agility element. I was ‘fading’ out the lure by using my hand with the treat to cue her to jump. At the time I had no understanding of ‘how’ I was training my dog. I just knew that it was fun to get her to do ‘tricks’ which I proudly showed off to my family.

Despite their applause I knew that I was not ‘really’ training her. It was just too easy, and I was using treats, surely ‘real’ dog trainers didn’t use food rewards to get dogs to do things. Getting a terrier to jump through a hula hoop or over a leg to reach the treat on the other side seemed like such a no-brainer and so easy that I couldn’t feel any pride in the achievement. There must other ways that trainers got dogs to perform tricks, ways that a kid like me knew nothing about.

At that time indeed there were. Trainers were instructing owners on the variety of different chains and collars to use to control and manage their dogs along with the size and material best suited for use as a truncheon to beat a dog that didn’t follow commands. These methods had percolated through our culture and were incorporated into some of the relationships I had with dogs. I once jammed my knee into a dog’s chest so forcefully when it jumped on me that when I re-entered the house and the dog cowered away from me I felt only embarrassment and regret when his owner complimented me for ‘training’ him to stop jumping.

On my sixteenth birthday I was given a puppy and could not have been happier. This eight week old ball of fluff and I were as inseparable as a dog and young teenager could be, and more than we should have been. I would regularly skip classes so I could sneak home and cuddle and play with her. I named her Treble and she was by anyone’s account a beautiful dog. She looked like a small, reddish-gold Belgian Malinois with feathers on her legs and tail. When questioned about her breed I responded that she was a ‘golden shepherd’, but she was just pure mongrel.

Though I never thought about training Treble she learned to sit, lie down, and would turn on a dime when I called her name, even if she was in pursuit of a squirrel, an activity which I encouraged during our visits to the Boston Common. Treble rode on the subway and wandered the streets of the city with me. I strolled on the beach while she tormented sea gulls pecking at debris along the tide line. I adored her and her seeming adoration of me. She was a dog, my precious dog, and nothing that she did ever seemed to me to be a punishable offense. Rather it was me that sneaked her into rooms, allowed her on beds, and into cars that had been designated off-limits to dogs, the tell tale fur left on bedspreads and upholstery earning me frowns and rebukes from my family.

When asked, as children often are, what I wanted to be when I grew up, I did not know how to respond. The only jobs that I was aware of that would have allowed me to spend time with dogs, which is what I would have preferred, were dog catcher (as they were called back them) or veterinarian. ‘Dog catcher’ was loaded with too many negative connotations, though today I have high regard for people who choose a career in animal control. I was allergic to cats and not interested in medicine. Dog training was limited to the military, police and ‘seeing eye’ dogs and ‘dog trainer’ had not made it into aptitude tests or onto the lists of high school guidance counselors.

Recently I discovered a film produced by a seventeen year old trainer by the name of Devi Stewart showing how she taught her dog Chaos to submerge its nose in a bowl of water and blow bubbles. To accomplish this she used a clicker and treats. I was impressed by and envious of this young trainer. More than thirty years after the thrill of getting a dog to jump over my legs, Devi was getting her dog to perform a ‘trick’ which would inspire professional trainers. I could not have begun to imagine how to teach a dog to do this when I was that age, but by applying the principles of positive reinforcement, i.e., dogs will repeat behaviors they get rewarded for, she made it look easy.

While I was living my life, accompanied by dogs, there had been an evolution in dog training. I envy Devi, and the young trainers like her, the years they have ahead of them during which they can hone and perfect their training skills and the pleasure they and their dogs will derive from it. As for me, I’m looking forward to learning a few new tricks myself in the years to come.